In this brief, we rank each state based on the level of prison education offered at state and private prisons and on their use of these policies. The ranking criteria focused on two main parts: 1) availability of educational programs and 2) implementation of key policies.

Policymakers should consider these findings and recommendations. Expanding and improving prison education is not only a matter of justice and rehabilitation but also a prudent investment in public safety and community well-being. By adopting these policies, states can actively use their prison systems to help rehabilitate prisoners and set them up for post-release success.

The United States has the world's largest prison population and spends billions annually on incarceration.[1] State policymakers could get more value from this expenditure by expanding access to education within prisons. This policy brief builds upon recent research, highlighting the benefits of prison education programs and state-level policy reform.

Prison education programs have been marked by significant policy shifts. Most notably, the 1994 federal Crime Bill, which barred incarcerated individuals from Pell Grant eligibility, led to a significant reduction in prison education programs, particularly college-level courses. This policy change resulted in a steep decline in educational opportunities for prisoners, impacting their post-release outcomes. However, in June 2023, the federal government restored access to Pell Grants for incarcerated students.[2] This is a testament to the growing acknowledgment of the benefits of prison education.

Disproportionately low literacy and education levels among prisoners underscores the importance of expanding access to education. Further, the largest meta-analysis of prison education research showed that effective prison education programs could directly reduce the costs of incarceration. They lower recidivism rates (by an average of 6.8 percentage points), improve post-release employment rates (by an average of 3.1 percentage points) and post-release annual earnings (by an average of $565).[3] The study showed that these programs pay for themselves in reduced costs from lower reincarceration rates.

Given the effectiveness of prison education, it is important to consider the role of public policy in promoting these efforts. In a corresponding study, we discuss three specific policies states can implement to enhance the effectiveness of education programs in prisons.[4] These include:

Automatic enrollment in educational programs for inmates lacking certain educational attainment.

Establishment of a school district or state office to oversee adult prison education.

Provision of sentence-reduction incentives for participation or completion of educational programs.

In this brief, we rank each state based on the level of prison education offered at state and private prisons and on their use of these policies.

Data for this project come from three sources. Data on prison characteristics come from the 2019 Census of Correctional Facilities.[5] We collected state-level data on whether states had administrative offices overseeing prison education and whether a state automatically enrolled prisoners in educational programs from official state websites. Data on state-provided sentence reduction for participation in educational programs come from the National Conference of State Legislatures.[6]

The ranking criteria focused on two main parts:

Availability of educational programs.

Implementation of key policies.

Each state was ranked for educational offerings based on the percentage of prisoners housed in a prison with each of the four main categories of educational programs: adult basic education (literacy), secondary (GED), vocational and college. For each category, states in the bottom 20% of educational offerings were given zero points, those in the second 20% were given 0.25, and so on. The top 20% received one point. This means that states could score between zero and four points based on the participation rates of these four types of educational offerings in a state.

Policy implementation was assessed on a binary scale. A state received one point for implementing each of the three recommended policies. Our analysis aimed to create a balanced evaluation of both the presence of supportive policies and the actual educational opportunities available to inmates.

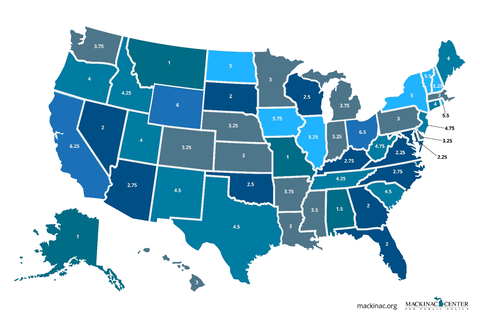

The table below presents the overall scores for each state. Scores range from Ohio’s 6.5, only half a point below the highest possible score, to 1.0 points awarded to Alaska, Missouri and Montana.

| Rank | State | Score | Rank | State | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ohio | 6.5 | 30 |

Hawaii | 3.0 |

| 2 | California | 6.25 | Kansas | ||

| 3 | Wyoming | 6.0 | Louisiana | ||

| 4 | Iowa | 5.75 | Massachusetts | ||

| 5 | Rhode Island | 5.5 | Minnesota | ||

| Vermont | Pennsylvania | ||||

| 7 | Illinois | 5.25 | 36 | Arizona | 2.75 |

| New Hampshire | Kentucky | ||||

| 9 | New York | 5.0 | North Carolina | ||

| North Dakota | 39 | Oklahoma | 2.5 | ||

| 11 | New Jersey | 4.75 | Wisconsin | ||

| West Virginia | 41 | Maryland | 2.25 | ||

| 13 | New Mexico | 4.5 | Virginia | ||

| South Carolina | 43 | Florida | 2.0 | ||

| Texas | Georgia | ||||

| 16 | Idaho | 4.25 | Nevada | ||

| Tennessee | South Dakota | ||||

| 18 |

Connecticut | 4.0 | 47 | Alabama | 1.5 |

| Maine | 48 | Alaska | 1.0 | ||

| Oregon | Missouri | ||||

| Utah | Montana | ||||

| 22 | Arkansas | 3.75 | |||

| Washington | |||||

| Michigan | |||||

| 25 | Mississippi | 3.5 | |||

| 26 | Colorado | 3.25 | |||

| Delaware | |||||

| Indiana | |||||

| Nebraska | |||||

Policies related to prison education programs and their implementation appear to vary considerably across states, influencing the availability and participation in prison education. The correlation between policy adoption and access to prison education is significant. States with recommended policies, such as automatic enrollment and dedicated oversight, exhibit higher rates of educational access.

States like Ohio and California, which have implemented all three recommended policies, demonstrate greater access across all types of prison education measured. Similarly, the low-scoring states typically performed poorly in both use of policy and educational offerings and participation. Of the 10 states that scored at or below 2.5, only South Dakota was above average in one the four educational categories, and only Florida had adopted more than one of the recommended policies.

The data also underscore the effectiveness of state-level policies in promoting prison education. Automatic enrollment ensures that those in obvious need of educational intervention are not overlooked. This helps bridge educational gaps within the prison population. Similarly, states with dedicated offices or school districts overseeing prison education programs, like Arkansas and Illinois, demonstrate their effectiveness by offering a diverse set of educational programs for inmates.

States with the highest scores are also notable in their diversity. They include small and large states, with and without large urban centers, and, politically, both red and blue states. This suggests that prison education has broad bipartisan support and could be expanded and improved in most political environments.

A full breakdown of each state’s score is available in the table in “Appendix A: Full state scores.” These scores are visually represented in “Appendix B: Map of state scores.”

Despite broad general support for these programs, reforming prison education systems has been slow. This has resulted in an uneven patchwork of policies and educational opportunities for prisoners. Given that prison education for non-federal prisoners is overseen almost entirely by states, we need to know more about what states are currently doing to expand educational opportunities in prisons.

This brief uses the 2019 Census of Correctional Facilities to measure the level of educational offerings and hand-collected data on state policies that effectively enhance educational opportunities. We find that large differences exist in the level of prison education across states. There is also a clear correlation between proactive state policies and access to prison education programs. States that have embraced these policies provide better educational opportunities for inmates and pave the way for more effective rehabilitation and reintegration into society.

Policymakers should consider these findings and recommendations. Expanding and improving prison education is not only a matter of justice and rehabilitation but also a prudent investment in public safety and community well-being. By adopting these policies, states can actively use their prison systems to help rehabilitate prisoners and set them up for post-release success.

| State | Education Availability | Policy Implementation | Total Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABE/Literacy | Secondary | Vocational | College | Automatic Enrollment | School District | Sentence Reduction | ||

| OH | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.5 |

| CA | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.25 |

| WY | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6.0 |

| IA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5.75 |

| RI | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5.5 |

| VT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5.5 |

| IL | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5.25 |

| NH | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5.25 |

| NY | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5.0 |

| ND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.0 |

| NJ | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4.75 |

| WV | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4.75 |

| NM | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4.5 |

| SC | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4.5 |

| TX | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4.5 |

| ID | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4.25 |

| TN | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4.25 |

| CT | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.75 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4.0 |

| ME | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.0 |

| OR | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4.0 |

| UT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.0 |

| AR | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3.75 |

| WA | 0 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.75 |

| MI | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3.75 |

| MS | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.5 |

| CO | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.25 |

| DE | 0.75 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.25 |

| IN | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.25 |

| NE | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3.25 |

| HI | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.0 |

| KS | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.0 |

| LA | 0 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.0 |

| MA | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3.0 |

| MN | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3.0 |

| PA | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3.0 |

| AZ | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2.75 |

| KY | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.75 |

| NC | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2.75 |

| OK | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.5 |

| WI | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2.5 |

| MD | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.25 |

| VA | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.25 |

| FL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| GA | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| NV | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| SD | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.0 |

| AL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 |

| AK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0 |

| MO | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| MT | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

[1] “Highest to Lowest - Prison Population Total” (World Prison Brief, n.d.), https://perma.cc

[2] “U.S. Department of Education to Launch Application Process to Expand Federal Pell Grant Access for Individuals Who Are Confined or Incarcerated | U.S. Department of Education” (U.S. Department of Education, June 30, 2023), https://perma.cc

[3] Ben Stickle and Steven Sprick Schuster, “Are Schools in Prison Worth It? The Effects and Economic Returns of Prison Education,” American Journal of Criminal Justice 48, no. 6 (December 1, 2023): 1263–94, https://perma.cc

[4] Ben Stickle, Steven Sprick Schuster and Emerson Sprick, “How States Can Improve Education Programs in Prisons” (Mackinac Center for Public Policy, 2024), https://www.mackinac.org

[5] “Census of State and Federal Adult Correctional Facilities” (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2019), https://perma.cc

[6] “Good Time and Earned Time Policies for People in State Prisons (as established by law)” (National Conference of State Legislatures, December 2020), https://perma.cc