Most Michigan residents would guess that the University of Michigan’s flagship campus in Ann Arbor is easily the most expensive of the 15 public universities in the state. After all, a student enrolled there for 15 credit hours typically pays more than $14,000 in annual tuition, compared to less than $9,500 at Northern Michigan University or Eastern Michigan University. But those numbers are often deceiving, because tuition varies with whether a student takes lower- or upper-division courses and, at many schools, with the number of credit hours taken during an academic term. Some schools are also generous with tuition discounts in the form of scholarships.

Compare the University of Michigan with Michigan State University. A student taking a 12-hour load will pay about $3,000 a year more to go to Ann Arbor – but a student taking a heavy 18-hour load will pay well over $2,500 a year more in East Lansing. That’s because tuition at Michigan is fixed for students taking 12 to 18 hours, in marked contrast to many other schools that charge by the credit hour. In other words, a student at Michigan has incentives to take a heavy load and graduate in a timely fashion.

Almost 85 percent of students who earn a bachelor’s degree from Michigan do so within four years, far more than the 64 percent at Michigan State and an extraordinarily low 34 percent at Wayne State University.

While these differences are revealing, the true cost of going to college depends not only on the number of years attended but also on the risk of dropping out. It is a fact that over half of the first-time undergraduates (non-transfers) entering seven of the state’s public universities never graduate, or at least not within six years. (The seven are Oakland, Wayne State, Eastern Michigan, Northern Michigan, Lake Superior State, Saginaw Valley State, and the University of Michigan-Flint.)

At Wayne State, a paltry 11 percent of students graduate in the standard four years, and only 32 percent graduate in six. The figures are only slightly better at Eastern. (There are major data limitations with respect to transfer students, and Wayne State’s performance mirrors that of similar urban state universities in nearby states.)

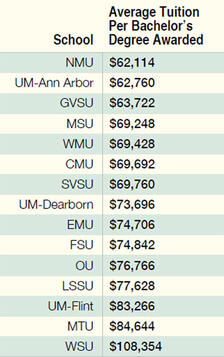

Taking these factors into consideration, we calculated a “tuition cost per degree” for the various state schools. This figure takes into account that many students pay a lot in tuition and fees but never get a bachelor’s degree.

Schools with seemingly high tuition rates, notably Michigan, turn out to be relatively less expensive when you factor in those students who pay tuition dollars but fail to graduate, or who take more than the standard four years. At least five state schools cost 20 percent more than Michigan by this criterion. The cost of Wayne State is particularly troubling. When the chances of graduating within even six years are less than one in three, one has to ask: Should the school be closed down in the interest of consumer protection and wastage of human resources? Does the Detroit area need five state universities, particularly when only one of them – the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor – manages to graduate a majority of its students in six years?

Why shouldn’t, for example, Eastern Michigan, with its less-than-40-percent graduation rate and its $20 million-plus annual tax on students to subsidize an anemic sports program located six miles from the Big House, be under intense legislative scrutiny?

Not only do students feel the true higher costs associated with low academic success rates, taxpayers do, too. They are silent partners in funding state schools, contributing importantly to the costs of running these enterprises. Are they getting their money’s worth? That is a question worth exploring.

#####

Richard Vedder directs the Center for College Affordability and Productivity, where David Holman is a research associate. Vedder also teaches at Ohio University, where Holman is an undergraduate student. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided that the authors and the Mackinac Center for Public Policy are properly cited.

The Mackinac Center for Public Policy is a nonprofit research and educational institute that advances the principles of free markets and limited government. Through our research and education programs, we challenge government overreach and advocate for a free-market approach to public policy that frees people to realize their potential and dreams.

Please consider contributing to our work to advance a freer and more prosperous state.