A trial court in Ohio recently held that Lake Erie beachfront property owners have the right to exclude others from their property. As the right to exclude is a traditional and fundamental aspect of owning property, it seems odd that such a holding would be newsworthy. But in 2005, the Michigan Supreme Court held that the general public has a right to walk the Great Lakes shoreline, and that trumps the property owners’ right to exclude. These divergent results indicate that there must be constant vigilance to prevent property rights from being weakened.

The Michigan Supreme Court in its 2005 Glass v. Goeckel decision held that Great Lakes property owners did not have the power to exclude beach walkers below the high-water mark. In making this ruling, the court relied on the public trust doctrine, which was originally meant to protect navigation and subsistence hunting and fishing. The Michigan Supreme Court created a new "public trust" right to walk on property below the high-water mark, which was ill-defined, both geographically and temporally. In that case, the court defined the high-water mark as "the point on the bank or shore up to which the presence and action of the water is so continuous as to leave a distinct mark either by erosion, destruction of terrestrial vegetation, or other easily recognized characteristic."

While the Glass case was winding its way through the Michigan courts, the state of Ohio was using the public trust doctrine to allow beach walkers below the high-water mark, and it was also charging adjoining owners rent for the property between the high-water mark and the water’s edge. In essence, Ohio claimed ownership over all land from the high-water mark to the water, even if landowners’ deeds said ownership extended to the water’s edge.

Not surprisingly, the Ohio tactic led to a lawsuit. A trial court in Ohio held that the public trust stops at the water’s edge, i.e., that the state had no interest in any privately owned dry land. In making this decision, the Ohio trial court, while not bound to follow Michigan decisions, looked at Glass and explicitly held that it was not persuasively decided. An appeal is almost certain.

These beach cases expose an invidious problem; the chipping away at property rights through government actions that fall short of full takings. When the government takes property for the public good, it is supposed to pay full compensation. Thus, when a farmer loses his land for a new highway, compensation is required. But when various limits are placed on the manner in which the property owner may use that property, generally no compensation is required. Government may be able to achieve many of the same goals without offering payment.

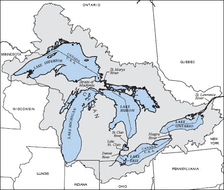

Consider the issue of the Great Lakes beachfront property. By the state not taking all the property below the high-water mark, the state is able to secure that property’s use without paying a dime for the purpose of allowing residents to walk on it. If the state were to condemn the 3,052 miles of Great Lakes shoreline (a figure that includes island shoreline), then the cost the state would pay would be astronomical.

Oft times the government will attempt to achieve its goals through regulations or legislation that limits property rights but does not fully take property. But state advancement of novel legal theories is another avenue. The Michigan expansion of the public trust doctrine might not have been able to be achieved through rule-making or the legislative process.

While many people are undoubtedly pleased with the Michigan result that allows the general public to walk on the beach below the high-water mark, we should not happily accept the erosion of one of the pillars of our society — the right to own property, which necessarily includes the power to exclude. The general public needs to understand that tomorrow the person losing their rights may not be their neighbor; it may be them.

The Ohio court is to be commended for being a bulwark against further property rights erosion. Unfortunately more work is needed to reacquaint the public with the fundamental role that property rights play in a free and fair society.

#####

Patrick J. Wright is senior legal analyst at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a research and educational institute headquartered in Midland, Mich. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided that the author and the Center are properly cited.

The Mackinac Center for Public Policy is a nonprofit research and educational institute that advances the principles of free markets and limited government. Through our research and education programs, we challenge government overreach and advocate for a free-market approach to public policy that frees people to realize their potential and dreams.

Please consider contributing to our work to advance a freer and more prosperous state.