Michigan's Prevailing Wage Act of 1965 requires contractors to pay artificially high union wages on all state-financed projects from road repair to school construction. This study examined the performance of Michigan's economy for two 30-month periods prior to and during the law's suspension by a federal district court and found that taxpayers could save hundreds of millions of dollars annually if the law were permanently repealed. The study also reveals prevailing wage laws' negative effect on job creation in the construction industry and their discriminatory impact on black and other minority workers. 21 pages.

In 1931, in the midst of the Great Depression, Congress passed the Davis-Bacon Act, a law that requires governmental contractors to pay "prevailing wages" on projects undertaken for the federal government. This legislation led to the passage of "little Davis-Bacon Acts," or "prevailing wage" laws in over 40 states, including Michigan.

What are prevailing wages? The short answer is that in many jurisdictions, including the federal government, prevailing wages are typically wages set at or near the union-scale level. Prevailing wage laws, then, force contractors on government construction or other projects to pay their employees at the same rate as unionized members of the relevant occupation—whether it be bricklayers, carpenters, electricians, or other categories of workers—even if non-union contractors could perform the same work less expensively by paying their workers lower but mutually agreed-upon wages.

In December 1994, a federal district court judge ruled that Michigan's prevailing wage law was preempted by ERISA, a federal pension law. Consequently, the state law was not enforced between 1994 and 1997. A subsequent appellate court decision reinstated the law in June 1997, making it possible to analyze the effects on the economy of both the law and its temporary repeal.

This study examined the performance of Michigan's economy in the 30 months that the prevailing wage statute was suspended and the 30 months prior to the district court's nullification of the law to determine the following:

Michigan's prevailing wage law reduces employment in construction: During the 30 months (December 1994 - June 1997) when the law was ruled invalid, more than 11,000 new jobs were created as a consequence of the law's invalidation—and the long term impact is much greater;

Michigan's prevailing wage law adds at least $275 million annually to the cost of governmental capital outlays—approximately the equivalent of five percent of the revenues raised from the state's individual income tax;

In 1990, African-Americans in Michigan were less than 50 percent as well represented in the construction industry as whites; black employment in Michigan construction was well below the national norm, reflecting both theoretical and empirical evidence that prevailing wage laws promote racial discrimination;

States without prevailing wage laws had net in-migration of over 2.5 million persons from 1990 to 1996, while strong prevailing wage law states like Michigan had out-migration of 2.7 million; nationally, poverty rates are higher in prevailing wage law states; and

Nationally, worker productivity appears to be lower in construction in states with strong prevailing wage laws, and construction costs are higher in public (prevailing wage) construction than in the private sector where market forces prevail.

Prevailing wage laws are poor economics and poor policy. They restrict people from operating in a free market to allocate resources and use factors of production most efficiently, thus retarding job creation and contributing to lower economic growth. As a result, people have been moving out of Michigan and other prevailing wage states, preferring to earn money in environments where their rate of pay is determined by their individual skills and worth, not by a governmentally determined "just wage" that bears little resemblance to economic reality.

Michigan's prevailing wage law was enacted over 30 years ago to deal with economic conditions that simply do not apply in the modern global economy. The preponderance of the evidence suggests that the Michigan legislature would be wise to repeal the Prevailing Wage Act of 1965.

In 1931, in the midst of the Great Depression, the U. S. Congress passed the Davis-Bacon Act, a law that requires governmental contractors to pay "prevailing wages" on projects undertaken for the federal government. This legislation led to "little Davis-Bacon Acts," or "prevailing wage" laws in over 40 states. Some states have subsequently repealed these statutes, but the majority, Michigan included, still have such Depression-inspired laws on the books regarding wages on state (and usually local) government contracts.

What are prevailing wages? The short answer is that in many jurisdictions, including the federal government, prevailing wages are typically wages set at or near the union-scale level. Prevailing wage laws, then, force contractors on government construction or other projects to pay their employees at the same rate as unionized members of the relevant occupation—whether it be bricklayers, carpenters, electricians, or other categories of workers—even if non-union contractors could perform the same work less expensively by paying their workers lower but mutually agreed-upon wages.

Typically, governments use an elaborate process to determine prevailing wages, but because of the large number of distinct geographic labor markets and numerous occupational categories, the tendency is for wages to be set equal or approximate to those determined in local collective bargaining agreements between unions and contractors. In some states, "prevailing wages" are less obviously tied to union pay scales, but Michigan, as a "strong" prevailing wage state, does use such a formulation.

Prevailing wage laws were first adopted during the Great Depression, at a time when the national unemployment rate was already about 14 percent and rising, while economic output was dropping.1 The turmoil brought about by such large numbers of unemployed workers gave rise to various arguments and theories about how government could solve America's economic woes.

One popular argument for prevailing wage laws was advanced by some in the Hoover administration. They (and later others in the Roosevelt administration) argued that by mandating higher wages for workers than what they might otherwise be paid according to market forces, workers would make higher incomes and therefore spend more. High wages would help America spend its way out of the Great Depression. This "high wage doctrine" was also advanced by many business leaders, and it formed the basis for many other pieces of legislation during both the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations (e.g., the National Industrial Recovery Act, National Labor Relations Act, etc.).

Another "argument" for the original Davis-Bacon legislation and no doubt many of the state prevailing wage laws was Northern union contractors' desire to be protected from competition from lower-wage, Southern, non-union workers. In fact, Rep. Robert Bacon was prompted to introduce his bill in 1931 after witnessing one contractor's use of black Alabama laborers to construct a government hospital in Rep. Bacon's Long Island district. A review of the legislative history of the Davis-Bacon Act makes it clear that the idea behind "prevailing wages" was seen by some congressmen as a way to reduce out-of-state competition and discourage the use of non-white labor. One congressman who supported Davis-Bacon actually made reference to the "problem" of "cheap colored labor" on the floor of the U. S. House. As such, the legislation was both anti-competitive and racist in origin.2

A third argument used to support prevailing wage laws—still advanced today—is that they reduce poverty, by insuring that construction or other affected workers earn enough income to stay above the poverty line. Finally, some pro-prevailing wage advocates have said that paying high wages insures quality work or, alternatively, that high wages lead to greater labor morale thereby promoting efficiency, and thus these laws cost little or nothing.

There is, however, both theoretical and empirical evidence that casts doubts on the arguments above and suggests that prevailing wage laws are outmoded, ineffective, discriminatory, inefficient, and expensive to taxpayers. The force of these arguments has led some states to abandon long-enacted legislation.

There are four theoretical arguments against prevailing wage laws. First, such laws force employers to pay compensation levels in excess of what workers might voluntarily agree to accept. The quantity demanded of construction labor varies inversely with its price—i.e., the cheaper labor is, the more workers employers will want to hire. This is the famous Law of Demand (see Graph 1). Conversely, the quantity of labor supplied tends to vary directly with its price (or wage): The more workers can earn in construction, the more persons will want to work those jobs. In a market without any legal impediments, wages will tend to be set at a level where the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. At that point, all workers truly seeking jobs and capable of doing the work are able to obtain employment. Economists refer to this point as "market equilibrium."

The enactment of a prevailing wage law forces wages up (to B in Figure 1), to a point where the quantity of labor supplied (S) exceeds the quantity of labor demanded (D). Put simply, prevailing wage laws create unemployment and reduce employment opportunities in the affected fields. The precise impact depends on a variety of factors, including the sensitivity of workers and employers to changing wages, as well as the extent to which prevailing wage laws apply in labor markets.

Second, where employers show discriminatory treatment toward workers on the account of their race, sex, age, or some other attribute, prevailing wage laws make it easier and less financially punishing for them to indulge their particular bigotry. Consider a state without a prevailing wage statute, where Contractor A wants to hire a plumber. He offers the generally agreed-upon, market hourly wage of $10 per hour and receives one job applicant, an African-American. Even if Contractor A possesses some racial prejudice, he almost certainly will hire the black applicant because he needs a plumber. To get more applicants in the hopes of attracting a preferred white worker, he would have to offer to pay more, thus lowering his profits. Now suppose a prevailing wage law sets plumber wages at an above-market rate of, say, $15 per hour. Contractor A gets three applicants, two white and one black. He can now hire a white worker without a financial penalty. In other words, prevailing wage laws remove the financial disincentive for employers to engage in racial discrimination since all workers must be paid according to the same wage rate.

Third, prevailing wages—being higher than wages normally agreed upon between employers and workers—should lead either to higher prices for contracted goods and services or to less of the goods being provided. For example, suppose it costs $5 million to build on average one mile of highway when contractors pay voluntary market wages, but $5.5 million when they pay government-mandated prevailing wages. Suppose further that a state highway department has a budget of $300 million for new highways. Without prevailing wages, 60 miles of road can be built; but with such wages, only 54 miles can be constructed. Thus prevailing wage laws tend to reduce real infrastructure investments. It is true that the state could spend $330 million so that no real reduction in highway construction need occur, but in that case the taxpayers are burdened more, through higher taxes and/or a reduction in other state budget priorities.

A fourth theoretical objection to prevailing wage laws relates to administrative issues. Nationwide, there are literally thousands of distinct local labor markets, and numerous occupations that come under the jurisdiction of the federal Davis-Bacon Act as well as state laws such as exist in Michigan. Moreover, wages change with some regularity. Thus there are literally tens of thousands of different wages that need to be evaluated to guarantee they meet the "prevailing wage" criteria, and this evaluation needs to be done on at least an annual basis to ensure accuracy. The complexity of such evaluation can drive administrative costs way up and open the door for fraud and abuse.3

The economic theorizing above suggests that prevailing wage laws should reduce employment in the affected areas, since at the above-market "prevailing" wage, some workers are not hired compared with the number that might be when employers and workers are free to negotiate wages themselves. This is a testable proposition. The one sector of the economy most affected by prevailing wage laws is construction. In a typical recent year, about one-fourth of all construction in the United States is carried out in the public sector, which faces prevailing wages under the Davis-Bacon Act and in many states, including Michigan, under state prevailing wage laws.4

The states can be divided into two categories, the first including the 18 states without prevailing wage laws, and the second the 33 states (counting the District of Columbia) with such legislation. Additionally, 12 states, including Michigan, can be subcategorized as having "strong" prevailing wage laws.5 Using these categories, the number of construction workers per 1000 jobs in 1993 in states with a strong, weak, or no prevailing wage law were compared (1993 is the last full year prior to Michigan having its prevailing wage law ruled inoperative by judicial decision).

Chart 1 shows that construction workers are far more prevalent in states without prevailing wage laws than in those with such statutes. The 18 states without any prevailing wage law (except, of course, for federal legislation) in 1993 had 44.38 construction workers per 1,000 workers, compared with 33.25 for the 12 states having "strong" prevailing wage jurisdictions. Michigan was one of the "strong" prevailing wage states.6 This is compelling evidence that supports the contention that prevailing wage laws reduce employment in the construction industry.

An alternative approach is to examine Michigan's experience for the period before the prevailing wage law was ruled invalid (in December 1994) and then for the period of two and one-half years in which the statute was inoperative (ending June 5, 1997, when the Michigan Appeals Court reversed the district court and reinstated the law).

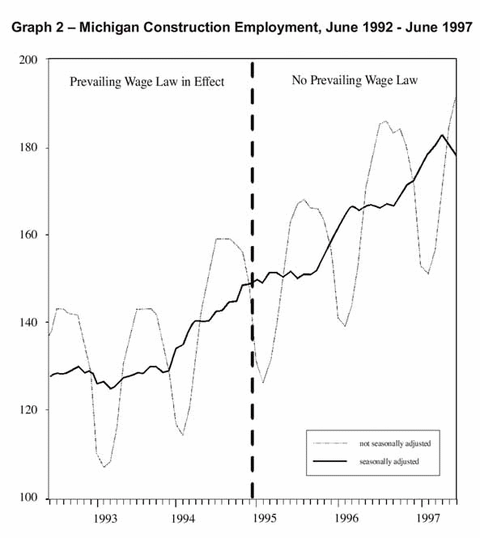

For this, monthly data on Michigan's aggregate employment, sectoral employment, total unemployment, and total labor force were gathered for the first eight years of the 1990s.7 The growth in employment in Michigan's construction industry in the 30 months prior to the court decision invalidating the prevailing wage law (June 1992 through December 1994) was then compared with a 30-month period during which the law was inoperative, from December 1994 to June 1997.

As Chart 2 shows, job growth in Michigan's construction industry was small in the prevailing wage period (4,000 jobs per year) compared with more than quadruple the jobs created (17,600 per year) in the brief period during which the prevailing wage law was inoperative. This suggests a sluggish rate of job growth during the era of wage restraints was followed by a marked expansion in the job market when those restraints were removed.

This conclusion, however, can be objected to on three grounds. First, there is seasonality in construction employment, and the periods chosen bias the results in favor of the conclusion that job growth expanded during the period with no prevailing wage law, since that period begins in a low employment winter month and ends during the summer, near the peak of the construction season. Second, employment in construction, and in general, is affected by the business cycle, so some consideration must be given to the impact of cyclical movements. Third and finally, weather could conceivably cause some of the observed trend. Suppose June 1992 was a great month weather-wise for construction, while December 1994 was a miserable one (independent of the season of the year). The sluggish growth in construction for the prevailing wage period might be explained by that phenomenon.

In order to control for possible seasonal, cyclical, and weather effects, a series of adjustments were performed using data for eight full years (96 months) from 1990 through 1997. A standard procedure was used to adjust the data for seasonal trends, the effect of which was to lower the reported employment figures for summer months and increase them for winter months when inclement weather makes it difficult to carry out construction activities.8

Graph 2 shows the actual (unadjusted) and the adjusted construction figures by month for the period June 1992 through June 1997. After seasonal adjustment, the 34,000 increase in the number of construction jobs during the era of no prevailing wages is sharply reduced, to 8,833 jobs (job growth was 20,747 in the prevailing wage era, compared with 29,580 in the post-prevailing wage era). Still, adjusting for seasonal factors, employment growth in construction expanded more than 42 percent during the period without the prevailing wage law.

Could that growth be explained by chance patterns in the weather? To largely correct for the impact of weather variation, the data were converted to three-month moving averages. For example, suppose December 1994 were unusually cold and snowy even for December, thus depressing the amount of construction employment. A three-month moving average is used to combine the seasonally adjusted construction figures for the months of October, November, and December. The figures are then averaged to produce December's moving average estimate—dramatically reducing the impact of abnormal weather in the single month of December.

Once the moving average adjustment is made, it turns out that the estimate of construction job expansion in the period of no prevailing wage laws actually increases by over four thousand workers—weather factors kept reported job growth during the December 1994 to June 1997 period lower than it otherwise would be. The estimate of increased job growth, making both seasonal and weather adjustments, rises to 13,017 jobs.

Might the growth in construction jobs be explained by the economic boom that picked up as the 1990s proceeded? The 1990-91 downturn reached a trough (bottom) in the spring of 1991, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the organization responsible for dating business cycles. Unemployment, however, actually kept rising into early 1992. Recovery was clearly underway by the fall of 1992, and the Michigan unemployment rate actually fell sharply during the 30-month period of prevailing wage laws from June 1992 to December 1994 (the unadjusted rate went from 9.3 to 4.8 percent), but not in the 30 months without the prevailing wage law (the unadjusted unemployment rate fell from 4.8 to 4.4 percent).

Employment growth, however, was moderately higher in Michigan in the period without the prevailing wage law: 277,800 jobs (seasonally adjusted) vs. 241,948 jobs in the earlier period. Thus some of the greater rise in construction employment in the period without prevailing wages is attributable to slightly more robust general employment growth reflecting cyclical conditions and the passage of time. Accordingly, the estimate of job growth during the suspension of the prevailing wage law was reduced by about 13 percent to account for the moderate general rise in employment growth in that period, yielding a total estimated construction job growth in the era of no prevailing wages of 11,337 jobs (see Table 1).

In other words, after adjusting for seasonal, weather, and cyclical considerations, it is estimated that construction jobs grew by over 11,000 during the no-prevailing wage period. Moreover, this estimate is probably highly conservative for a variety of reasons, the most important of which is that there was considerable uncertainty whether the December 1994 judicial interpretation that rendered the prevailing wage law invalid would be sustained upon appeal. In an environment where employers knew with certainty that there would be no prevailing wage legislation, they probably would have moved even more aggressively to take advantage of the changed legal environment.9 The national data on construction employment in non-prevailing wage states presented in Chart 1 are consistent with the view that the total long-term construction employment impact of a repeal of the prevailing wage law could well be a multiple of three or even four times the 11,000 jobs created during the period in which prevailing wages were ruled invalid in Michigan.

Given the uncertain nature of the 1994 invalidation of the prevailing wage law, the robustness of construction employment growth during the era of no prevailing wages was really quite extraordinary. Once the data are corrected for seasonality and weather (using a moving average), construction employment growth is shown to be much greater after the prevailing wage law was invalidated. As Chart 3 shows, in the first period when prevailing wage laws were operative (June 1992 to December 1994), 78.61 construction jobs were created for each 1,000 increase in total employment. In the era without an operative prevailing wage law (December 1994 to June 1997), there were 116.27 construction jobs created per 1,000 total new jobs, an increase of nearly 48 percent.

Who are the individuals who gain new jobs when prevailing wage laws are ended, as they temporarily were in Michigan from December 1994 to June 1997? Both the economic theory cited earlier and empirical evidence nationally suggest that it is likely that a disproportionate number of new jobs will go to minorities. Removal of wage requirements allows relatively less experienced minority workers a chance to offer their services at lower rates than the artificially determined prevailing wages, obtaining employment and the on-the-job training that leads to higher productivity and earnings in the long run.

Prevailing wages raise labor costs. The impact that they have on total construction costs depends on three factors:

1) the extent to which prevailing wages exceed the wages that employers and workers would otherwise voluntarily agree upon;

2) the proportion of labor costs in the total costs of construction; and

3) the impact, if any, that prevailing wages have on worker productivity.

Turning first to the issue of the extent that prevailing wages exceed the wages that employers and workers would otherwise voluntarily agree upon, the evidence is that prevailing wages are very well over 50 percent above market wages—for example, $16 per hour vs. $10 per hour. To be sure, some workers might be hired at union-scale wages in the absence of prevailing wage laws, and other workers (e.g., supervisors) are not affected by the laws, so the aggregate impact on payroll may be less, but it is still significant.

This generalization applies in Michigan. Tables 2 and 3 show that, for two populous Detroit-area counties, prevailing wages for many construction occupations tended to be substantially above the wages voluntarily negotiated between employers and workers.

On average, it appears that labor costs equal 20 to 30 percent of total construction contracts, with the proportion somewhat lower for single family housing.10 If labor costs were 25 percent of the total value of a construction contract, and if on average labor costs per hour were increased 40 percent by prevailing wage laws, this would drive up total construction costs by about 10 percent—assuming that paying prevailing wages does not change the physical productivity of workers. (There is no reliable evidence that labor productivity is materially different where prevailing wages exist, a point considered below.) The 10-percent figure accords with several studies of the impact of prevailing wages on construction costs. It may actually be conservative, since the 40-percent compensation differential assumed may well be below the average for prevailing wage contracts.

During the 30-month period of no prevailing wages in Michigan, there is evidence of numerous government construction projects being carried out with significant savings arising from the use of non-union scale labor. For example, in the Hastings school district in Calhoun County, the lowest open shop (non-union) bid was $4,343,000—almost 13 percent below the lowest union bid of $4,969,000.11

There are also examples of even greater savings associated with non-union labor. In Saginaw County, a Carrollton public school renovation project received a non-union bid of $645,000, which was more than 16 percent below the lowest union bid of $774,000. To be sure, in some cases the savings from the use of non-prevailing wage labor were less, but they were always real and positive. On average, over 20 different projects, the savings were well above the 10-percent figure used in some calculations of taxpayer burden below.

Assuming the 10-percent differential and that the "construction cost" portion of capital outlays by Michigan state and local governments equals the outlays for activities subject to prevailing wages, in fiscal year 1995, the state of Michigan and its localities could have saved about $251 million by eliminating prevailing wage provisions, since construction outlays for Michigan governments in fiscal year 1995 were $2,509,684,000. Alternatively, some $251 million more in social infrastructure could have been completed.12

Presumably, some non-construction capital outlays were also subjected to prevailing wages, such as renovation work considered as heavy maintenance (e.g., replacing a roof on a school building). If one were to assume that 20 percent of the non-construction capital outlays were subject to prevailing wages and that the average savings of eliminating prevailing wages were 10 percent, the savings to taxpayers for the public projects undertaken in Michigan in 1995 would be about $275 million.

A savings of $275 million is no small sum of money: It is the equivalent of slightly over five percent of the revenue raised by the Michigan individual income tax in fiscal year 1995 ($5.473 billion). Assuming things have not changed dramatically since 1995, repealing Michigan's prevailing wage law would have an impact the equivalent of giving every taxpayer a rebate equal to five percent of his state income tax payments. The continued existence of prevailing wage laws therefore has a potentially real and important impact on the well being of the residents of Michigan.

The calculations above are extremely cautious and conservative. A majority of the government construction projects examined by this author showed potential savings of greater than 10 percent associated with the elimination of prevailing wages. The year examined, fiscal year 1995, was one in which the prevailing wage law was invalidated for part of the year, so some work may have already been undertaken outside the prevailing wage environment (if all work had been under prevailing wages, construction outlays may have been higher).

National data on construction costs reinforces the notion that the 10-percent savings estimate is probably extremely conservative. Chart 4 shows that construction costs per square foot for projects generally undertaken in the public sector (e.g., school buildings, general public buildings) tend to be dramatically higher than those undertaken in the private sector (e.g., commercial or manufacturing buildings).

The added expense that prevailing wages impose upon school construction projects frustrates officials in many Michigan school districts because it may make it more difficult for them to gain approval of important bond issues from skeptical taxpayers. Statewide in 1998, only 44 out of 107 proposed school bond proposals worth $2.2 billion were approved by voters.13 James Kos, superintendent of Hamilton Public Schools in Allegan County, argues that a repeal of the prevailing wage law could save his district "between one and $1.5 million in construction costs and we' d be able to use that money for students."14

Some will argue, however, that prevailing wages improve worker morale and provide a more skilled labor force and raising productivity, in keeping with a concept called "efficiency wages" that is much discussed by some modern "new" Keynesian economists.15 To get some sense of the productivity of construction workers, state government data on construction workers were gathered from the U. S. Department of Labor and data on the value of construction contracts were gathered from the U. S. Department of Commerce. The average productivity of workers in the "no prevailing wage" and "strong prevailing wage" states was then compared by dividing the value of construction contracts in 1997 by the number of construction workers.

As Chart 5 indicates, output per construction worker was actually about four percent higher in the states without prevailing wages, suggesting that the existence of such laws may lead to inefficiencies and reduced productivity, enhancing our confidence in stating that prevailing wage laws materially raise the costs to taxpayers. If anything, these data suggest that the savings from eliminating prevailing wages may be materially greater than the 10 percent figured used in the calculations above. For that reason, the author believes that a 5 percent reduction in the Michigan individual income tax could easily be financed from the savings from elimination of the Michigan prevailing wage law.16

Earlier it was suggested that prevailing wages should reduce employment opportunities for groups subject to racial discrimination, such as blacks. The historical evidence is that from the very beginning some proponents of the Davis-Bacon Act and companion state legislation wanted to reduce construction employment for African-Americans.17 Although a detailed examination of this issue as it pertains to Michigan is beyond the scope of this study, some descriptive statistical evidence is consistent with the view that the Michigan law has disadvantaged blacks more than whites.

Chart 6 shows for Michigan and the nation the number of construction workers per 1,000 total employed for both blacks and whites, using data from the 1990 Census of Population.18 Note that for both blacks and whites, there were fewer construction workers in relation to the total labor force in Michigan than in the nation as a whole, but that the disparity was particularly striking for blacks. The percentage of blacks working in construction (here defined as "construction trades" and "construction laborers") was over 40 percent below the national norm. For whites, the disparity was less than 20 percent.

Employment in general in Michigan construction was lowered because of the negative consequences of strong prevailing wage laws, as well as possibly other factors, as discussed above. Yet employment was particularly reduced for blacks, consistent with the theory that prevailing wage laws reduce financial disincentives for employers to discriminate by race. Nationwide, blacks in 1990 were 74 percent as well represented in construction as whites (as measured by the percent of workers working construction). That underrepresentation may well reflect the discriminatory impact of the national Davis-Bacon Act as well as individual state prevailing wage laws.

The Michigan strong prevailing wage law, however, seems to compound the racial effects. In Michigan, blacks in 1990 were less than 50 percent as well represented in construction as were whites. The Michigan figure is well below that for the nation as a whole. While other factors could be at work here, it is not known what they are. There is very strong, even compelling, circumstantial evidence that the Michigan prevailing wage law has reduced employment opportunities in particular for blacks.19

Prevailing wages were supposed to reduce poverty and improve living standards for workers on government-funded projects, typically construction. If such laws are "good," they should raise the quality of life and promote in-migration in the relevant state. Construction workers, their relatives, and others would want to go to the high-wage areas protected by prevailing wage legislation. If, however, the laws reduce employment, raise costs of construction, and increase burdens on the taxpayers, one would expect the laws to have a negative impact on the quality of life in a state and thus lead people on balance to leave the state.

What is the evidence for the 12 states that are "strong" prevailing wage law states, a group that includes Michigan? Chart 7 shows that from 1990 to 1996, some 2,676,800 native-born Americans migrated out of the "strong" prevailing wage law states for other states. That is the equivalent of over one thousand persons moving each day, every day for those six years. Where did these people move? Almost entirely to the states with no prevailing wage laws—those states had net in-migration of 2,541,800 persons.

It is true that simple statistical comparisons such as this one need to be interpreted cautiously. States with prevailing wage laws may have other factors that tend to repel people from moving into them, for example.20 Nonetheless, this simple statistical observation suggests that the evidence favors those who support abolition of prevailing wage laws.

Other measures of economic well being also tend to leave a negative impression of prevailing wage laws. For example, from 1988 to 1996, per capita income rose on average 49 percent in the states without any prevailing wage, compared with 42.9 percent in the states with strong prevailing wage laws, a group that includes Michigan.

Originally, advocates of prevailing wage laws argued that they alleviated poverty. What is the evidence? As Chart 8 demonstrates, the poverty rate in 1994 in the states with no prevailing wages was actually lower than in the states with strong prevailing wage laws. While not conclusive, this evidence suggests that, if anything, prevailing wages raise poverty rates, presumably by denying job opportunities to some low-income potential workers.

The state of Michigan has a strong prevailing wage law, albeit one that is still under legal challenge. An examination of the evidence on employment, construction costs, and even broader economic effects suggests that state prevailing wage laws have adverse consequences. They cause significant unemployment in the construction industry. The temporary invalidation of the Michigan law resulted in more than 11,000 new construction jobs being created, and the permanent removal of the legislation likely would have more substantial employment effects.

Both economic theory and empirical evidence suggest that minority workers will particularly gain from the removal of prevailing wage restrictions. The severe underrepresentation of blacks in the Michigan construction industry is shameful, and in significant part likely arises because of the state's prevailing wage law.

It is estimated that in fiscal year 1995, the Michigan prevailing wage law increased the costs of public capital outlays by at least $275 million, equal to five percent of individual income tax collections that year. Significant tax relief and/or expansion of public infrastructure would be possible if the Michigan law were permanently repealed.

Prevailing wages restrict people from operating in a free market to allocate resources and use factors of production most efficiently, thus retarding job creation and contributing to lower economic growth. People have been moving out of Michigan and other prevailing wage states, preferring to earn money in environments where their rate of pay is determined by their individual skills and worth, not by a governmentally determined "just wage" that bears little resemblance to economic reality. The original prevailing wage laws were conceived two-thirds of a century ago to meet problems that do not exist today. Michigan's law was enacted over 30 years ago to likewise deal with economic conditions that simply do not apply in the modern global economy. The preponderance of the evidence suggests that the Michigan legislature would be wise to repeal the Prevailing Wage Act of 1965.

The author acknowledges the research assistance provided by Joshua Hall, graduate student in economics at Ohio University, and the additional assistance of Mackinac Center staff members including Director of Labor Policy Robert P. Hunter and Labor Research Assistant Mark L. Fischer.

Dr. Richard Vedder is Distinguished Professor of Economics at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. He has written extensively on labor issues, authoring such books as The American Economy in Historical Perspective and, with Lowell Gallaway, Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America.

Dr. Vedder has written over 100 scholarly papers published in academic journals and books, and his work has also appeared in numerous newspapers and magazines including the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Investor's Business Daily, Christian Science Monitor, and USA Today.

Dr. Vedder has been an economist with the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, with which he maintains a consulting relationship. He has served as the John M. Olin Visiting Professor of Labor Economics and Public Policy at the Center for the Study of American Business at Washington University in St. Louis and has taught or lectured at many other universities.

For monthly unemployment rates during the Depression, see Richard K. Vedder and Lowell E. Gallaway, Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America, Updated Edition (New York: New York University Press, 1997), p. 77.

For a more detailed review of the racial dimensions of the Davis-Bacon Act, see Richard Vedder and Lowell Gallaway, Cracked Foundations: Repealing the Davis-Bacon Act (St. Louis: Center for the Study of American Business, October 1995).

The problems of administration and fraud are covered extensively in two hearings jointly held by the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations and the Subcommittee on Workforce Protections, both of the Committee on Education and the Workforce, U. S. House of Representatives. The first was held on June 20, 1996, and is reprinted as Joint Hearing on the Davis-Bacon Act: Focusing on Allegations of Fraud and Barriers to Employment in Serial No. 104-79 (Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office, 1996). The second, entitled Joint Hearing to Review the Davis-Bacon Act was held on July 30, 1997, and is reprinted in Serial No. 105-68 by the Government Printing Office in 1997. In the first hearing, see especially the testimony of Brenda Reneau, Oklahoma Commissioner of Labor. In the second hearing, read especially the statements of Charles C. Masten, Inspector General, U. S. Department of Labor and George S. Werking, Assistant Commissioner in the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the Labor Department.

In 1996, for example, public construction was over $141.1 billion, almost precisely one-fourth the total new construction of $568.9 billion. See the U. S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1997, p. 715.

On the "strength" of state prevailing wage laws, see A. J. Thieblot, "A New Evaluation of Impacts of Prevailing Wage Law Repeal," Journal of Labor Research, 17(2), Spring 1996, p. 317. The states with strong prevailing wage laws are Michigan, Illinois, Missouri, Rhode Island, Minnesota, Ohio, Washington, Hawaii, California, New Jersey, New York, and Massachusetts.

Michigan's law was invalidated late in 1994, too late to have any material impact on construction employment. Similar results are obtained using 1993 data, when Michigan unambiguously was covered by prevailing wage legislation the entire year.

The author thanks the Michigan Bureau of Consumer and Industrial Services and Mark L. Fischer and Robert P. Hunter of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy for their assistance in providing data.

The seasonal adjustment procedures were done using the Econometric Views computer software, following standard procedures used by the U. S. Department of Commerce and other federal government agencies.

Some employers probably reasoned that if the appellate court reversed the district court decision, they potentially might be liable for extra wage payments if they paid less than the prevailing wage, thus they behaved as if the prevailing wage law were still in effect.

See U. S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Construction Industries, 1992, or the 1997 Statistical Abstract of the United States, p. 713.

The author is indebted to the Associated Builders and Contractors of Michigan for this information.

The governmental revenue and expenditure data reported here were obtained from the U. S. Bureau of the Census World Wide Web site, www.census.gov.

For information on how school districts can earn the voter trust essential for needed bond proposals, see Michael Arens, The Need for Debt Policy in Michigan Public Schools (Mackinac Center for Public Policy, May 1998), accessible by Internet at www.mackinac.org/article.asp?ID=363.

Quoted in "Kuipers: End prevailing wage law: Representative says move could save millions," The Holland Sentinel, April 8, 1999, p. A1.

A standard reference is George Akeroff and Janet Yellin, Efficiency Wage Models of the Labor Market (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

To be sure, there would be some budgetary complications that would have to be resolved, such as the fact that capital outlays are financed by motor fuel taxes, property taxes, and other revenue sources. Some reduction in those levies might be appropriate in lieu of the income tax reduction used here for illustrative purposes.

Much attention has been given to a Utah Study that purports to show that repeal of prevailing wage laws would raise costs to taxpayers. See P. Phillips, G. Mangum, N. Waitzman, and A. Yeagle, Losing Ground: Lessons from the Repeal of Nine "Little Davis-Bacon Acts," (Salt Lake City: University of Utah, 1995). Thieblot, op. cit., has decisively refuted the claims and methodology in the Utah study. A detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this study.

The Michigan prevailing wage law dates only from 1965, when deliberate attempts to use laws to promote racially discriminatory behavior had largely passed from the scene. This does not negate the possibility, however, that the Michigan law could have had unintended adverse consequences for members of minority groups.

See the U. S. Bureau of the Census, 1990 Census of Population: Social and Economic Characteristics (Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office, 1993), Vols. CP-2-1, pp. 81-82, and CP-2-24, pp. 209-210.

See Robert P. Hunter, "Union Racial Discrimination is Alive and Well," Mackinac Center for Public Policy Viewpoint on Public Issues 97-26, September 1997, accessible by Internet at https://www.mackinac.org/article.asp?ID=325.

One factor closely associated with prevailing wage laws is unionization. The average percentage of the work age population that was unionized in the strong prevailing wage states was 11.20 percent compared with 4.26 percent in states without prevailing wage laws. For good data on the economic impact of unions, see Barry T. Hirsch and David A. Macpherson, Union Membership and Earnings Data Book (Washington, D. C.: Bureau of National Affairs, 1998).