One hundred years ago this December, Wilbur Wright placed himself at the controls of the airplane he and his brother had built, for what was to be the first self-propelled, controlled flight in history. Upon takeoff, the machine lifted up some 15 feet, stalled and crashed into the sand. It was to be another two days before the first successful flight took place, with Orville — not Wilbur — at the controls. Nearly forgotten to history, Wilbur’s aborted flight — one of the first airplane accidents in history — underscores the aviation industry’s century-long struggle for safety.

Despite the vast media coverage given to aviation accidents, the aviation industry has achieved breathtaking success in improving air safety. In the industry’s embryonic era, accidents were disturbingly numerous. Ironically, 1929, the year of “The Great Crash,” was also one of the most crash-ridden in aviation history, with 24 fatal accidents reported. In both 1928 and 1929, the overall accident rate was about one per every million miles flown. In today’s system, an accident rate of that magnitude would result in a nearly incomprehensible 7,000 fatal accidents each year.

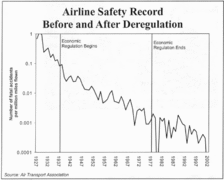

The next 70 years saw a rapid reduction in accidents as technologies improved and operating practices were perfected. By the 1940s, the annual number of fatal accidents averaged between five and 10. By the 1970s, the average was less than five. Last year, there were no fatal aviation industry accidents at all.

Even more impressive has been the reduction in the accident rate, which has been falling exponentially. By the 1930s, the rate was about a tenth of its 1928-9 level. Within another 20 years, the rate was a tenth of that — around one accident per hundred million miles flown. Since 1997, the rate has been at or below one in 2 billion.

How did airline deregulation affect these trends? In 1978, when federal controls over the rates charged and routes served by airlines were lifted, opponents charged that the action would lead to ballooning accident rates. Faced with competition, they argued, airlines would cut corners on safety in order to cut costs.

Yet, almost a quarter-century since the Airline Deregulation Act was passed, the industry’s safety record shows no sign of degrading. In fact, air travel is today substantially safer than in 1978. In the 24 years since economic controls were eliminated, the average number of fatal accidents has been 3.2 per year. In the 24 years before deregulation, the industry averaged almost double that: 6.2 per year. The difference in the accident rate is even more dramatic, with airlines averaging 0.0007 fatal accidents per million miles post-deregulation, barely a seventh of the rate for the 24 previous years.

This doesn’t mean that deregulation itself necessarily enhanced air safety. The broad trend line of safety improvement, in fact, seems to have continued at more or less the same rate before and after deregulation. (Similarly, despite an initial drop, the long-term trend hardly varied before and after the introduction of controls in 1938). In fact, it may be impossible to say with precision what would have happened had there been no reform. What is clear, however, is that the grim predictions of disaster by market opponents did not come true.

Why were they wrong? One reason is that the gloomsayers misread the incentives facing businesses in a competitive market. Rather than scrimp on safety measures to gain short-term profits, airlines have found it even more in their interest to ensure the safety of their passengers. Simply put, no one makes money by putting passengers in danger. Airlines such as Air Florida and ValuJet learned that lesson the hard way. In short, markets provide what consumers demand — and air travelers demand safety most of all.

There is, of course, room for improvement in air travel safety: in preventing crashes, and in ensuring security in the post-Sept. 11 world. But, as we approach the 100th anniversary of flight, we can also stop to take pride in the safety achievements of the past century, and the inventors and entrepreneurs who made it possible.

# # #

(James L. Gattuso is research fellow in regulatory policy at the Heritage Foundation in Washington, D.C., and an adjunct scholar with the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a research and educational institute headquartered in Midland, Mich. More information is available at www.mackinac.org. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.)

The Mackinac Center for Public Policy is a nonprofit research and educational institute that advances the principles of free markets and limited government. Through our research and education programs, we challenge government overreach and advocate for a free-market approach to public policy that frees people to realize their potential and dreams.

Please consider contributing to our work to advance a freer and more prosperous state.